“Twas the night before Christmas….” I’m sure we all can finish that line. “A Visit from St. Nicholas” was an important part of the Christmas holiday when I was a child. But finding out that Clement Clarke Moore is my 4th cousin, 8 times removed, makes it even more special to me now.

Early life and family

Clement Clarke Moore was born on 15 July 1779, at Chelsea House, his maternal grandparents’ estate in Manhattan, New York City. He was the only child of the Right Reverend Benjamin Moore, D.D., and Charity Clarke Moore.1

Clement was born into a privileged life. His father, the Right Reverend Benjamin Moore, was an Assistant Minister at Trinity Church in Manhattan and received the Doctor of Sacred Theology degree from Columbia University shortly before his birth.2 Rev. Moore became the Bishop-Coadjutor of the New York Diocese in 18013 and Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the State of New York later that year.4 A fuller accounting of the life of Bishop Moore was told in Part 3 of this series.

An only child, Clement was capably tutored at home by his father until he entered Columbia College, according to his biographer. Samuel White Patterson, he graduated in 1798 "at the head of his class, as his father had, thirty years earlier." In 1801 he earned his MA from Columbia University: he was awarded an LLD in 1829.

As the child of a clergyman, religion and religious activities would have been central to Clement’s life. Although he did not follow his father into ministry, his religious instruction during his youth shaped his future.

Clement married Catherine Elizabeth “Eliza” Taylor, the daughter of the late William Taylor and Elizabeth Van Cortlandt Taylor on 20 November 1813. Clement and Eliza became the parents of nine children.5

Eliza left behind a wonderful piece of poetry that illustrates the relationship she had with Clement:

Clement C. Moore

MY REASONS FOR LOVING.You ask me why I love him?

I’ll tell the reason true:

Because he said so often

With fervour “I love you.”

I loved him, yes, I loved him

Because he told his flame

With such a skilled variety

And whispered “Je vous aime.”

Because so sweetly tender

As any swain on Arno,

In crowded streets he’d woo me,

With Petrarch’s own “Vi amo.”

Because whenever coldly

I’d answer him “Ah, no,”

He’d all my coldness banish

By faltering “Te amo.”

Because when belles surrounded

He’d still address to me

The words of love and learning,

And sigh “Philea se.”

Because his English, French,

Italian, Latin, Greek,

He crowned with noble Hebrew

And dulcet “Ahobotick.”6

Sadly, Eliza died on 30 April 1830 at age 35. Their daughter, Charity Elizabeth Moore, died on 12 December of the same year.

Chelsea

When Clement’s mother died in 1838, she left him the Clarke family estate in Manhattan called Chelsea. The name is instantly recognizable by anyone who has visited or lived in New York City as the part of the city North of the West Village and South of Midtown and Hell’s Kitchen. From Colonial times into the 1800s, it was largely farmland and orchards owned by the Clarke family.

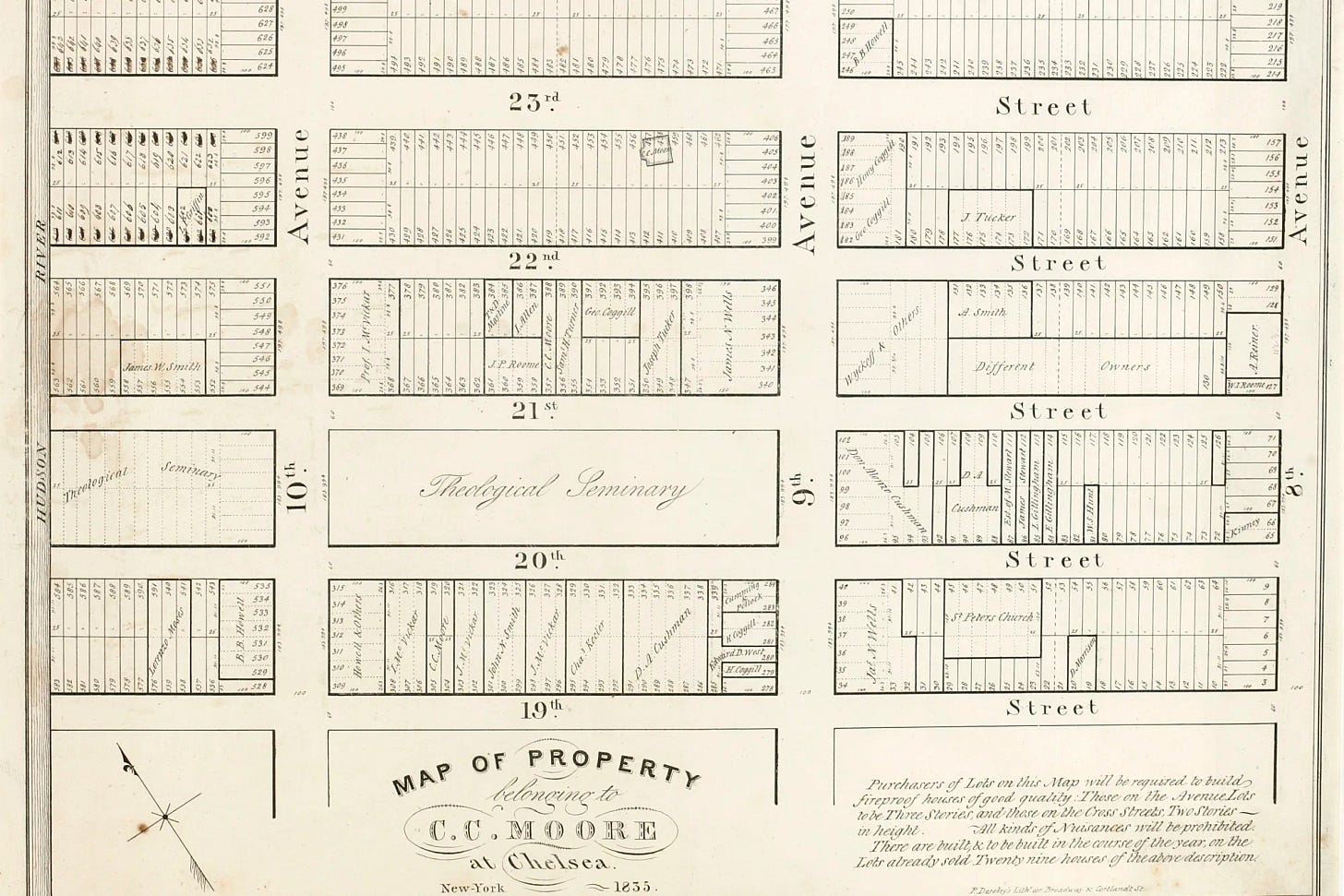

Moore himself was born in 1799 on a Manhattan farm established by his grandfather, Major Thomas Clarke, who named his property Chelsea in honor of a famous veterans’ hospital in London. Clarke’s daughter, Charity, married Benjamin Moore, who became bishop of the Episcopal church in New York. Clement Moore inherited the Chelsea estate from his grandfather, which spanned what today would be roughly from 19th to 24th streets between Eighth and 10th avenues — when he was just 14 years old.

Two years earlier, the city had created a map — the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 — that both created the city’s rectangular street grid and established the norm of 25-by-100-foot house lots.

Young Clement wasn’t happy with that denser future. In 1818, when he was 19 years old, he published an anonymous pamphlet titled “A Plain Statement, Addressed to the Proprietors of Real Estate, in the City and County of New-York,” calling the street plan a “source of stress and vexation.” He also predicted laying out the grid would be “expensive” and “obnoxious” and — when it was all over — the commissioners would have destroyed New York.

To keep the city from riding roughshod over his farm, he took the central orchard and donated it to the Episcopal Church to build the General Theological Seminary, established in 1817. But that still left much of Moore’s land ripe for development. As the 1820s progressed and New Yorkers began moving uptown, Moore began to have second thoughts about the evils of real estate. Instead of visions of sugar plums, he saw dollar signs.7

Beginning about 1820, Clement began making a series of donations of property that helped change his farmland into one of Manhattan’s premier residential and commercial neighborhoods. “In 1820, he co-founded and served as senior warden of closer-by St.-Luke-in-the-Field in Greenwich Village, the builder of which, James Wells, was to become his partner in developing Chelsea. A musician since childhood, he played the organ at St. Luke and was on the organizing committee for a couple of Handel and Haydn oratorios downtown.”8 In 1827, he donated 66 tracts of land that were the former apple orchard to the New York Episcopal Diocese to establish the General Theological Seminary. In 1837, he donated the land to build St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Chelsea at 20th Street and 9th Avenue. He served as a professor at the seminary for many years afterward.9

“A Visit from St. Nicholas”

In December 1823, the Troy Sentinel newspaper in upstate, Troy, New York, published an anonymous poem called “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” The poem quickly gained popularity and spread across the nation. It wasn’t until 1844 that Clement Clarke Moore claimed authorship of the poem when he included it in Poems, a collection of his poetry. He said that he had written the poem to read to his children on Christmas Eve in 1822.10

In the years since then, family members of Major Henry Livingston, Jr., and some academics have claimed that Major Livingston had written the poem. He, like Clement Moore, had written other poems for his children, but he did not claim authorship of the poem during his lifetime, and friends could not recall that he had ever mentioned writing it.11

Interestingly, he is credited with having written another Christmas poem in 1821. While not as light and cheerful as “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” it does provide some evidence pointing toward his authorship.

Old Santeclaus

Clement Clarke Moore

Old Santeclaus with much delight His reindeer drives this frosty night, O’er chimney-tops, and tracks of snow, To bring his yearly gifts to you. The steady friend of virtuous youth, The friend of duty, and of truth, Each Christmas eve he joys to come Where love and peace have made their home. Through many houses he has been, And various beds and stockings seen; Some, white as snow, and neatly mended, Others, that seemed for pigs intended. Where e’er I found good girls or boys, That hated quarrels, strife and noise, I left an apple, or a tart, Or wooden gun, or painted cart. To some I gave a pretty doll, To some a peg-top, or a ball; No crackers, cannons, squibs, or rockets, To blow their eyes up, or their pockets. No drums to stun their Mother’s ear, Nor swords to make their sisters fear; But pretty books to store their mind With knowledge of each various kind. But where I found the children naughty, In manners rude, in temper haughty, Thankless to parents, liars, swearers, Boxers, or cheats, or base tale-bearers, I left a long, black, birchen rod, Such as the dread command of God Directs a Parent’s hand to use When virtue’s path his sons refuse.This poem is in the public domain.

I doubt that authorship of “A Visit from St. Nicholas” is something that will ever be conclusively decided. Written documentation is lacking on both sides of the controversy. For my part, the book I had as a child said it was written by Clement Clarke Moore. That’s the one I’ll believe unless someone can provide positive proof otherwise.

Later Life and Retirement

When Clement retired from his position as a professor at General Theological Seminary in 1860, he began spending most of his time at his 25-room Victorian summer home in Newport, Rhode Island. He died in Newport on 10 July 1863. He was first buried in the graveyard adjacent to St. Luke-in-the-Field but was moved to the Trinity Church Cemetery in Uptown Manhattan when the graveyard at St. Luke was redeveloped in 1891. Clement’s funeral was held in Trinity Church where his father preached for many years.

Since 1911, a unique Christmas tradition has been observed at Moore's grave. Initiated by Vicar Milo Hudson Gates, the ceremony involves children gathering around Moore's gravestone to sing Christmas carols and place wreaths. This tradition, which originally involved children carrying lanterns and torches, continues into modern times, connecting generations of New Yorkers to Moore's literary legacy.12

Finding that Clement Clarke Moore is one of my ancestors was a delightful shock. We had joked in our family about the possibility, but never really considered that it could be true. But writing a children’s Christmas poem is not why he should be remembered. His contributions to building important areas of New York City should be celebrated. The General Theological Seminary is a wonderful respite in the busy city I occasionally visited to think and escape. I will thank him for it on my next visit.

Charles H. Weygant, The Sacketts of America, their ancestors and descendants, 1630-1907, (Newburgh, New York, 1907), 125, imaged by Internet Archive, Library of Congress (https://archive.org/details/sackettsofameric02weyg/page/n127/mode/2up).

Herman Griswold Batterson, A sketch-book of the American episcopate, (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1878), 66, imaged by Google (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nnc1.cr59971983&seq=76).

Ibid., 66-67.

Weyant, The Sacketts of America, 125.

William Ogden Wheeler, The Ogden Family, Elizabethtown Branch, (Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott, 1898), 196, imaged by Google, (https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Ogden_Family_in_America_Elizabethtow/lTPH48yu-b4C?hl).

Mary Moore Sherman, transcriber, Recollections of Clement C. Moore, (New York, Knickerbocker Press, 1906), image William and Mary Digital Archive (https://melvilliana.blogspot.com/2017/12/clement-c-moore-my-reasons-for-loving.html).

James Nevius, “How ‘Night Before Christmas’ creator also spawned NYC’s Chelsea,” New York Post, 18 December 2019, (https://nypost.com/2019/12/18/how-night-before-christmas-creator-also-spawned-nycs-chelsea/).

Justin Fox, “A Gift for America’s Christmas Poet: Rehabilitation,” Bloomberg Opinion, 22 December 2021, (https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-12-22/-night-before-christmas-author-clement-c-moore-s-shot-at-rehabilitation).

General Theological Seminary, “History,” (https://www.gts.edu/our-history), accessed 26 April 2025.

“Clement Clarke Moore, 1779-1863,” Poetry Foundation, website (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/clement-clarke-moore), accessed 26 April 2025.

Ibid.

“‘Twas The Night: A New York Christmas tradition in an uptown cemetery,” The Bowery Boys, 14 December 2022, (https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2022/12/the-new-york-christmas-tradition-in-an-uptown-cemetery.html#google_vignette).

What a fabulous legacy that is. Nice to see the portraits of Clement and Catherine as well.

Love the poems Bill!