At the end of Part 2, you met my 3rd cousin, 9 times removed, the Rt. Reverend Benjamin Moore, D. D. In this part of my family story, we’ll watch Benjamin during the Revolutionary War and afterward in the new nation’s first capital, New York City.

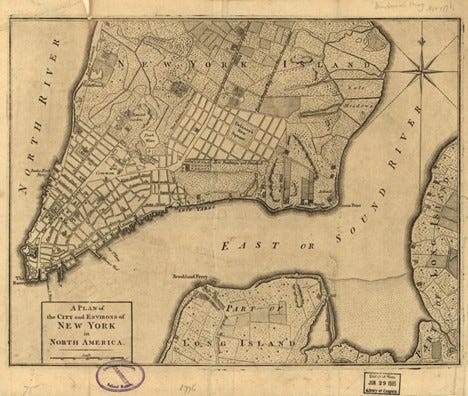

New York City was occupied by British forces from 1776 to 1783, who made it a central hub for their operations. Residents faced overcrowding, hunger, and harsh conditions, especially as thousands of Loyalists and soldiers flooded the area.

While British officers dined and enjoy (sic) a newly revitalized theater scene, Washington’s spies on the streets of New York collected valuable intelligence. As thousands of soldiers and sympathizing Loyalists arrived in the city, hunger and overcrowding put the residents of the city in peril. When the sugar houses and churches became too filled with captured rebels, the British employed prison ships along the Brooklyn waterfront to hold their enemies.1

When the new Reverend Moore returned to New York City to begin his ministry as an assistant rector at Trinity Church, he would have found the atmosphere to be much changed. The Boston Tea Party had happened just a year earlier. Punitive laws were increasingly enforced by the British authorities, as a result, the New York Committee of Correspondence was formed on 20 January 1774. This committee, and ones like it across the colonies, served to improve communication among the colonies and to coordinate activities in opposition to British rule.2

As a minister in the Church of England, Benjamin would have taken several oaths that required him to be faithful to the British Crown. Among these oaths would have been the Oath of Supremacy, acknowledging the monarch as the head of the church, and the Thirty-Nine Articles of Faith, defining the church’s position on religious and temporal matters.3 There could be no confusion about which side of the growing conflict the clergy would take.

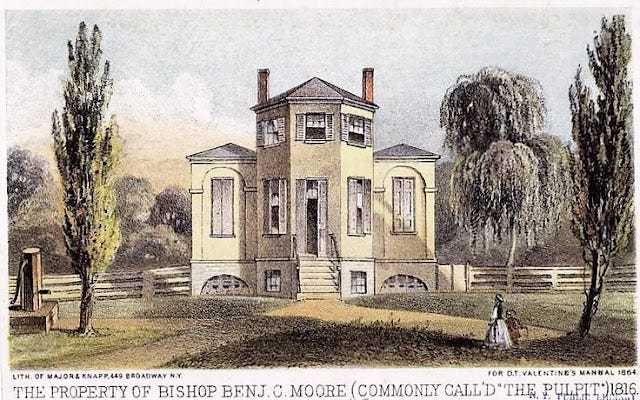

Benjamin married Charity Clarke, the daughter of British Major Thomas Clarke and his wife Mary Stillwell Clarke, on 20 March 1779.4 Mrs. Moore inherited a home and a large amount of property called “Chelsea” in Manhattan when her mother died in 1802.5

In November 1883, Rev. Moore was elected rector of Trinity Church after the prior rector and other clergy members fled to Canada before Washington’s troops retook New York City. But Rev. Moore’s election was contested by members who questioned his loyalty to America. Instead, the Right Reverend Samuel Provoost DD was installed as rector, and Rev. Moore returned to his position as assistant rector.6

After Dr. Provoost stepped down from the rector position in 1800, Rev. Moore was elevated to the rector’s position at Trinity Church. He held that position until his death. On 7 September 1801, Dr. Provoost resigned his position as bishop, but the resignation was not accepted by the house of bishops of the Church of England. Rev. Moore was, instead, elected Coadjutor Bishop of New York. When Bishop Provoost died in 1815, Bishop Moore became the second Bishop of New York.7

Bishop Moore was also very involved in higher education in New York. He served as president pro tempore of King’s College (now Columbia University) in 1775-76. He received the Doctor of Divinity degree from Columbia in 1801 and served as president of the university from 1801 to 1811. Additionally, he was a regent of the State University of New York from 1787 to 1803.8

On 15 July 1779, Benjamin and Mary Stillwell Moore had a son. They named him Clement Clarke Moore. You will learn about him in Part 4 of this series.

Mary Stillwell Clarke Moore died in 1802. Bishop Benjamin Moore died on 27 February 1816. He is buried at Trinity Church in New York City.9

Greg Young, “New York City during the Revolutionary War: Besieged and occupied by the British (1776-1783), The Bowery Boys Podcast, June 29, 2018 (https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2018/06/new-york-city-during-the-revolutionary-war-beseiged-and-occupied-by-the-british-1776-1783.html), accessed 19 April 2025.

“1774 — The Intolerable Acts, Continental Congress, and Prelude to War,” American History Central, website, (https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/1774-timeline-american-revolution-era/), accessed 21 April 2025.

“Oaths of Loyalty to the Crown and Church of England,” The National Archives, website, (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/oaths-loyalty-crown-church-of-england/), accessed 21 April 2025.

Rossiter Johnson and John Howard Brown, eds., The Biographical Dictionary of America, Volume VII, (Boston: American Biographical Society,1906), 451 “Benjamin Moore,” imaged: Internet Archive (https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Biographical_Dictionary_of_America,_vol._07.djvu/451).

“Chelsea House, Manhattan, New York,” American Aristocracy,” (https://americanaristocracy.com/houses/chelsea-house), accessed 21 April 2025.

Johnson and Brown, The Biographical Dictionary of America, Volume VII, 451.

Ibid. 451.

Ibid. 451.

Ibid. 451

This is truly fascinating information about your family and early New York. So, is it believed that the Chelsea area of NYC is still called such after Chelsea House, belonging to Mary Stillwell Clarke?

Yes. I'll be covering that in next week's installment, among other interesting items.