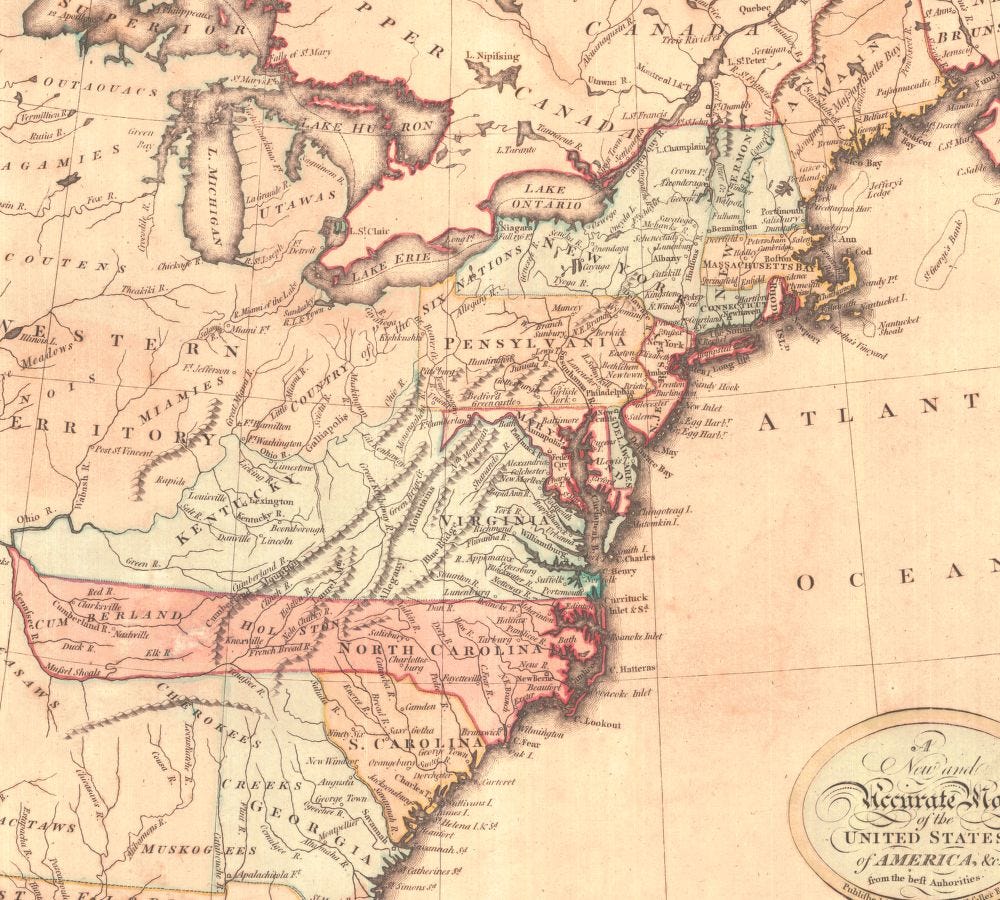

The early 1800s were a period of rapid growth in America. After a prolonged war for independence from Britain and several smaller wars with various Native American tribes (frequently spurred on by the British or the Spanish governments), a period of relative calm allowed adventurous settlers to begin a westward migration. It’s important to remember that land northwest of the Ohio River and west of the Mississippi was largely controlled by various tribes and could be inhospitable to new settlers.

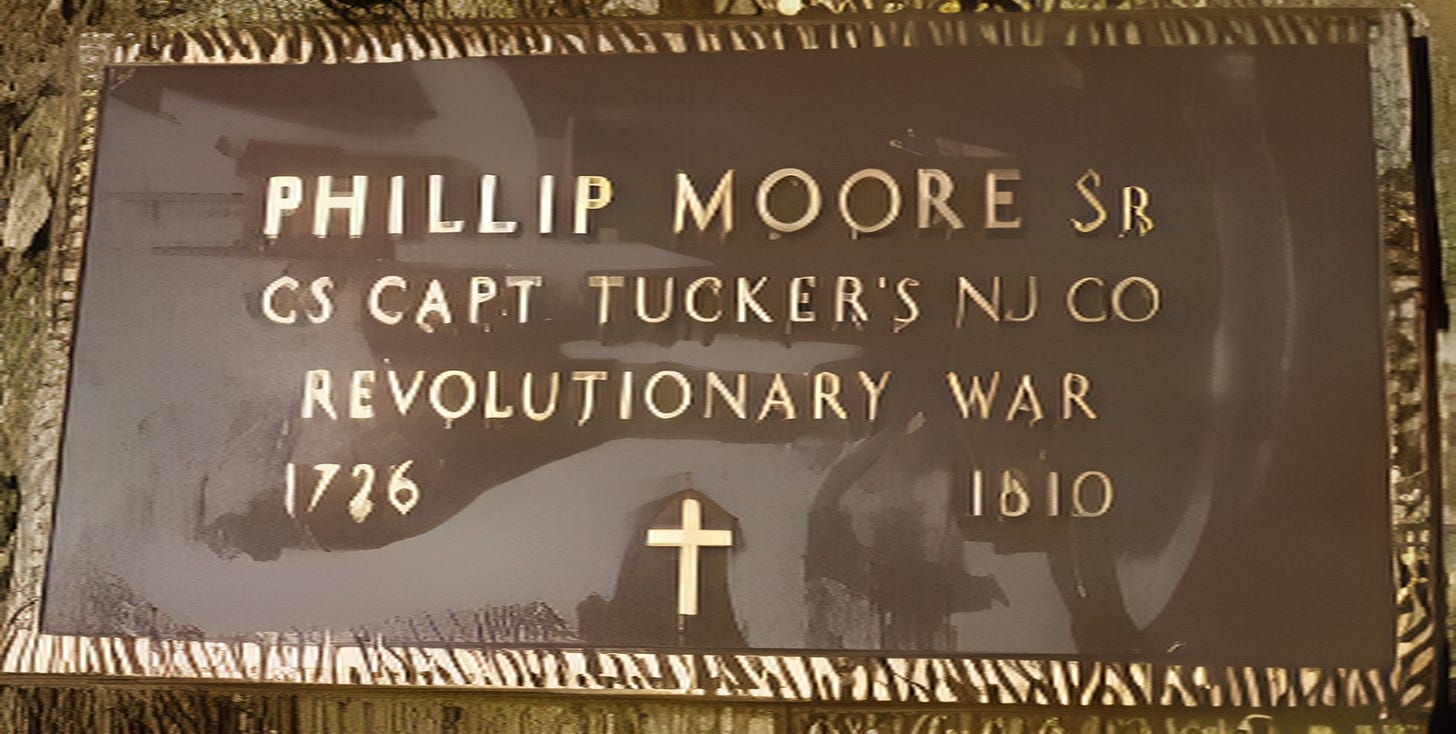

Philip Moore was born in Maidenhead, Hunterdon County, New Jersey, in 1726. He was the second of five children of Thomas Moore and Esther Phillips Moore.

He married Eleanor “Nelly” Evans. Information as to the date and location is not available at the time of this writing. They became the parents of Philip Moore, Jr. in 1755 in Hunterdon County, New Jersey.1

Revolutionary War Service

Like most men his age, Philip took an active role in military service during the Revolutionary War. Answering the call of the Provincial Congress of New Jersey in 1775, Philip became one of the famed “Minute Men.” This forerunner of today’s National Guard required that civilian militiamen be ready at a moment’s notice to gather at their captain’s front door. From there, they would go to their assigned battle locations. Hunterdon County had eight companies. Philip was assigned to Captain Tucker’s company.2 3

As the war progressed, the Hunterdon companies were called to duty on the eastern New Jersey shore, across from Staten Island, New York. This posting required about a week’s travel time to and from their posting, creating a burden on their families back home. In 1776, the war became very real for the New Jersey militiamen. They were called upon to augment the Continental Army troops, taking part in the Battle of White Plains. Several of the New Jersey soldiers were either killed or captured. 4

After December 8, central New Jersey was essentially under British occupation. Although many inhabitants had fled to Pennsylvania, some militiamen remained at or near home to protect their families and land. Many men had to decide whether it was better to see their life’s work destroyed or sign Howe’s loyalty oath and risk censure by their neighbors. They had seen firsthand the shrinking and disheveled American army, and some had served in it and experienced its defeats. Many must have believed the whole enterprise was over—even Washington expressed thoughts along those lines in his personal correspondence.

Despite Howe’s campaign to win back the loyalty of the rebels, British soldiers continued to plunder indiscriminately. After the American army crossed the Delaware to Pennsylvania on December 7, the British army was cantoned between Princeton and Trenton. At midnight on December 8 a large force marched through Pennington and on to Coryell’s Ferry (Lambertville) to seize boats the British army could use to cross the river and follow Washington. (None were found because American militiamen had secured every boat within many miles of the ferry.) During this foray, British soldiers raided the homes of Samuel Stout and John Phillips, both of whom lived just south of Coryell’s Ferry and had sons in the First Hunterdon militia. They destroyed Stout’s “deeds, papers, furniture and effects, of every kind, except what they plundered. They took every horse away, left his house and farm in ruins, injuring him to the value of two thousand pounds, in less than three hours. Old Mr. Phillips, his neighbour, they pillaged in the same manner, and then cruelly beat him.5

Moving Westward

When Thomas Moore died in 1793, he left Philip and his brother, John, his plantation in Maidenhead, New Jersey, and all movable stock. Philip inherited 2/3 of the estate. But by this time, the plantation had been farmed for many years, and the soil would have been largely depleted of nutrients to support new crops. The prospect of farming untouched land to the west would be an attractive opportunity. It appears that Philip and his younger brother, John, decided to take advantage of that opportunity after the death of their mother, circa 1797.

We have not found many records documenting the route the Moore families would have taken. With the help of ChatGPT, we can approximate the route that seems most likely.

The first leg of the journey would probably have taken 7-10 days from Maidenhead to Harrisburg via Philadelphia and the Lancaster Pike. The first part of the trip would largely be on good roads through rolling countryside. There were inns and taverns along the way to allow respite from the journey.

At Harrisburg, the Moore families joined members of Jemina Lewis’ family and of her former in-laws who would all be making the move to Ohio or beyond.

Gigantino, James J. II, ed., The American Revolution in New Jersey: Where the Battlefront eets the Home Front, p. 17, New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press, 1983, (https://dokumen.pub/the-american-revolution-in-new-jersey-where-the-battlefront-meets-the-home-front-9780813571935.html).

Stryker, William S., Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Revolutionary War, p. 694, Trenton, NJ: William T. Nicholson & Co., Printers, 1872.

Moore, James W., Rev. John Moore of Newtown, Long Island, and some of his Descendants, Easton, PA, Printed for the publisher by the Chemical Publishing Company, 1903.

Gigantino. p 20.

Ibid. p. 22.