My Moore Family in America - Part 11

The Journey West: The John B. Moore Family's Experience in Ohio and Indiana (1806-1840)

Life in Portsmouth, Ohio (1806-1835): A Developing River Town

During their nearly three decades in Ohio, the John B. Moore family would have experienced life in a community transitioning from a raw frontier outpost to a burgeoning regional center, deeply influenced by its strategic location on the Ohio River.

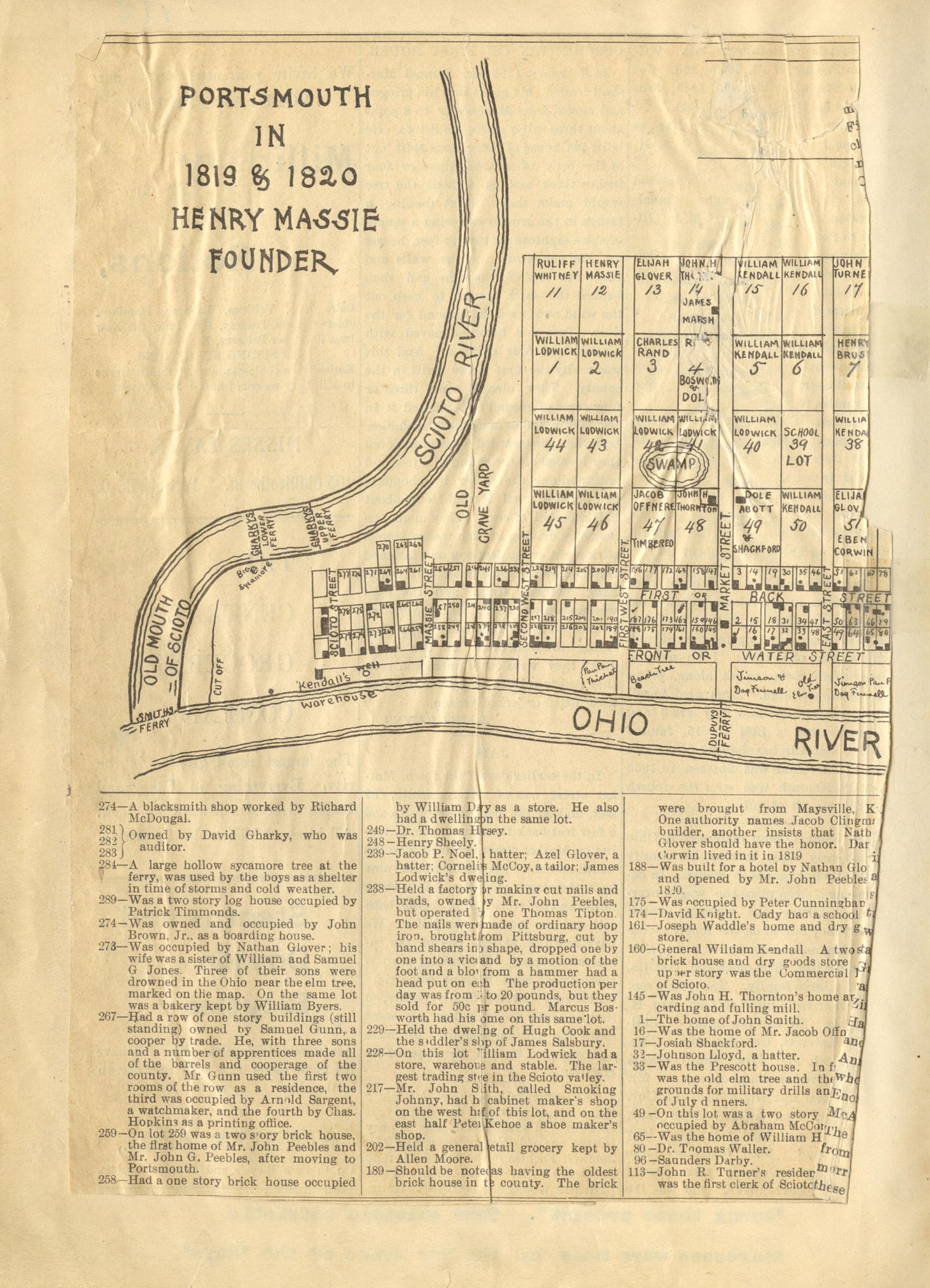

Portsmouth was formally platted in 1803 by Henry Massie, who strategically chose a location slightly east of the earlier settlement of Alexandria, aiming to avoid the frequent flood plains that plagued the older site. The town quickly grew, achieving incorporation as a city in 1814 and being designated as the county seat. This rapid formalization and civic development were largely attributable to its prime geographical position at the confluence of the Ohio and Scioto rivers. This confluence provided crucial access for transportation and trade, establishing Portsmouth as a vital hub in the burgeoning Ohio Valley. The surrounding terrain, part of the Western Allegheny Plateau, was notably hilly.1

Community institutions in early Portsmouth were nascent but evolving. While the establishment of public schools did not occur until 1838, earlier educational opportunities were available through fee-based schools, with the first recorded instance being a log house school established in 1823.2

The economic and civic progress experienced by white settlers often occurred in parallel with, and sometimes was predicated upon, the restriction and dispossession of other populations. This demonstrates that the "frontier" was not a uniform space of universal opportunity but a contested zone where the "creation of American identity" was a complex and frequently inequitable process, shaped by competing ideals of freedom and control. Despite these exclusionary policies, Portsmouth also played a role as an important hub on the Underground Railroad, aiding fugitive slaves seeking freedom in the North or Canada.3

For families like the Moores, the economic foundation of life in early 19th-century Ohio was primarily agricultural, with most farms geared towards subsistence production for family use. The monumental challenge for settlers was transforming the dense, forested wilderness into arable farmland, a task often undertaken with very limited material and physical resources. This arduous labor involved girdling thick-trunked beech trees to kill them and allow sunlight to reach the ground, clearing smaller brush, and scratching up the soil for planting. Common crops included corn, essential for both human consumption and livestock feed (especially hogs), as well as wheat, flax, and tobacco. Over time, families would also acquire hogs, sheep, and cattle.

Early on, dietary supplements were crucial, with families relying on foraging for wild walnuts and hickory nuts from the woods. Peach cultivation, surprisingly, became remarkably successful; by 1805, peaches planted from stones were so abundant that "millions of peaches rotted on the ground". A distinctive "cider culture" emerged, particularly for less prosperous settlers. Planting apple trees from seed was common, yielding apples that were often "gnarled and bitter" but immensely valuable for self-provisioning. These could be converted into pork by feeding them to hogs, or pressed into juice, cider, or cider vinegar. A simple cider press was frequently one of the first pieces of farm technology a new Ohio family acquired or constructed. Even more prosperous farmers who cultivated commercially valuable grafted fruit often found that poor transportation limited their profitability, leading much of this finer fruit to also be used for animal feed or cider production.4

By 1835, southern Ohio, including the Portsmouth area, had undergone significant transformation and was no longer the "wild" frontier it had been when the Moores arrived in 1806. The state had become "thoroughly domesticated" and its lands cleared for farming over decades, with certain areas increasingly industrialized. This maturation meant that the initial opportunities for acquiring vast tracts of virgin, fertile land, which characterized the earliest frontier phases, would have diminished considerably.

The Moores Migrate to Indiana

The Moores' decision to leave their established home in Ohio for Indiana would have been influenced by a combination of factors pushing them from their current environment and pulling them towards the perceived promise of a new frontier.

The evolving nature of the "frontier" itself was a key driver of continuous migration. The understanding that Ohio was "thoroughly domesticated" by 1800 implies that the frontier was not a static geographical boundary but a moving line, a dynamic concept. For families like the Moores, who had resided in Ohio for three decades, the initial opportunities and characteristics of the "first frontier" they encountered had likely been exploited or diminished. The notion of "depleted land" suggests that even if land was nominally available, its quality or the effort required to make it productive might have increased, pushing farmers to seek newer, more productive soils. This highlights a cyclical pattern of migration, where settlers continuously sought the "next" frontier as older areas matured, driven by a persistent pursuit of fresh agricultural opportunity and the perceived advantages of less-settled territories.

The migration of the John B. Moore family appears to have been done in connection with at least two other families from Scioto County, who will become relatives in the future. Land purchases in Delaware County, Ohio, in the 1830s show that George Truitt and Lloyd Wilcoxon purchased land adjacent to or near John and Lewis Moore.5

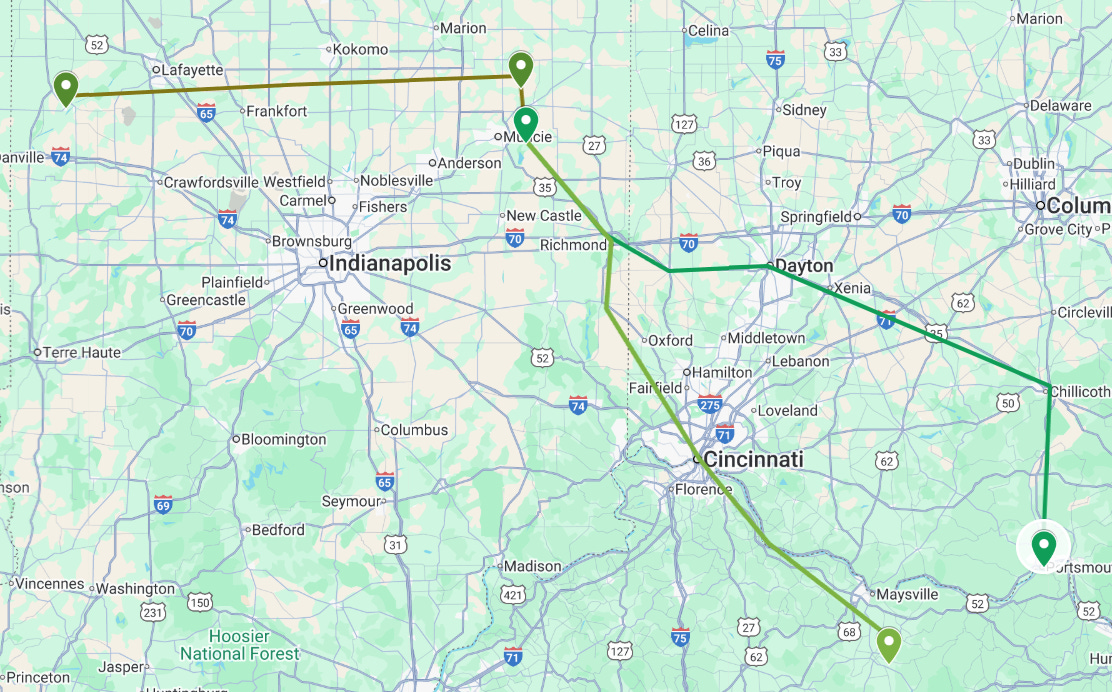

The exact route taken by the families is not known, but a few assumptions can be made. Roads from Portsmouth to Chillicothe and then to Dayton were well-established. From Dayton to Delaware County, Indiana, the group would likely have followed old Indian trails and less-reliable paths. They may have had to clear some vegetation to allow their Conestoga wagons to pass.

The pioneers from Scioto County, Ohio, would have found Delaware County, Indiana, to be a relatively untamed place. The area had long been the home of the Delaware (Lenape) Indian Tribe who were being forced from their land as they had been forced out of Ohio in the late 1700s.

Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, the Lenape were forced further and further from their homelands. Between 1778 and 1830 the Lenape governing bodies that would become known as Delaware Tribe of Indians and Delaware Nation were party to over 15 treaties with the United States that moved them from Ohio to Indiana, into Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, Texas, and eventually Oklahoma. Each treaty agreement was eventually broken or forced into renegotiation, as the United States proceeded with westward expansion. Lands the Lenape were promised became reclaimed by the United States again and again without fair compensation.6

The settlers would once again have to clear the land they purchased to build their houses and to prepare to plant crops in the coming seasons. The Moore family was well-equipped for the task. John and Nancy had plenty of help. Ten of their eleven children who survived into adulthood joined them on the move. (Nancy must have been a very strong woman. Her first child was born in 1810, the last in 1834 when she was 46.)

John Moore founded the first public school in Delaware County. In 1831, he sent his son William Jackson Moore (my 3rd great-grandfather) to live with a relative in Wayne County to attend school. When William arrived in Wayne County, he found that the school had closed and returned home to Smithfield. Shortly afterward, John converted an old log cabin on his property into a schoolhouse. He organized the area parents to subscribe to pay a teacher for two months to educate their children. 7

Sadly, Nancy Jackson Moore died on 28 November 1838. John followed her on 18 May 1840. Only three of their children were adults by that time. It appears that the younger children lived for some time with their eldest sister, Catherine Ann Moore Calvert. About 1845, two sets of the Moore young men struck out on their own. Levi and Milton moved south to Fleming, Kentucky. Philip and Enos moved a few miles north to Niles, Indiana. Enos eventually moved further west to Williamsport, Indiana, near the Illinois border.

Bean, Jonathan J., “Marketing ‘the great American commodity’: Nathaniel Massie and Land Speculation on the Ohio Frontier, 1783-1813,” Ohio History Connection, (https://resources.ohiohistory.org/ohj/browse/displaypages.php?display%5b%5d=0103&display%5b%5d=152&display%5b%5d=169), Accessed 22 June 2025.

City of Portsmouth, Ohio, “Portsmouth,” (https://www.sciotocountyoh.com/cities/portsmouth), Accessed 22 June 2025.

Wikipedia, “Portsmouth, Ohio,” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portsmouth,_Ohio), Accessed 22 June, 2025.

Kerrigan, William, “Creating Ohio’s Fruitful Landscape: 1800-1860,” Filson Historical Society, (https://filsonhistorical.org/wp-content/uploads/kerrigan-filson-fruitful-landscapes.pdf), Accessed 22 June, 2025.

Kemper, G. W. H., A Twentieth Century History of Delaware County, Indiana, Chicago: Lewis Publ. Co., 1908, p. 245. Imaged by HathiTrust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081821302&seq=271&q1=%22John+Moore%22), Accessed 19 June, 2025.

Delaware Nation, “The History of Delaware Nation,” (https://www.delawarenation-nsn.gov/history/), Accessed 22 June 2025.

Kemper, p. 247.

The Ohio Frontier by Douglas Hurt is a great primer on Ohio history. It recounts in detail every known atrocity against and from the Indians. One is left with a deeply sad understanding that there were psychopathic killers on both sides of the conflict. And about 95% of the Indians and whites alike were bystanders caught in the grip. With regard to your difficulty in tracking the move of your family to Indiana, this problem is made difficult by the fact that every five years or so the trails and routes shifted for a variety of reasons.