Some of my earliest memories are of visiting my great-grandmother in Wichita Falls, Texas. When I was young, we lived in Tulsa, Oklahoma. My father’s parents lived there, too. But my great-grandmother was our nearest maternal relative. She and my mother had always been close, so we visited there as often as time and finances would allow. My visits with her continued when I grew up, until shortly before she passed.

Her name was Sarah Ellen Ingham Boardman. But we called her Marney. I’m not sure who originally gave her that nickname. My mother called her “Mother.” My best guess is that it started with my mother’s cousins. At any rate, that is how we knew her.

Visiting Marney was an experience in every sense of the word. We knew we would have adventures with her. We also knew she would put us to work. And we loved every minute of it.

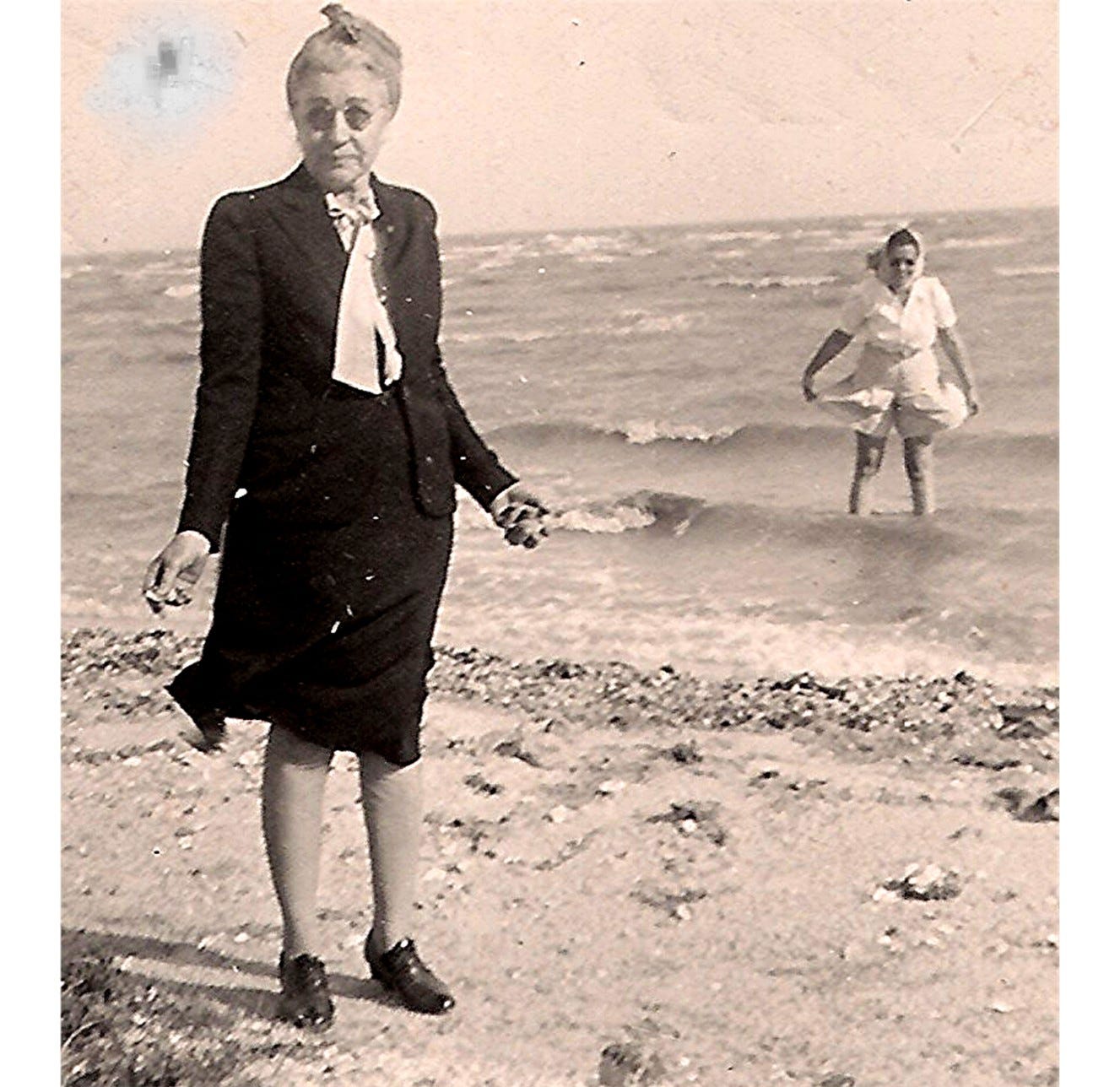

Marney dressed for the beach, circa 1950. Photo collection of the author.

Marney’s Home

Wichita Falls, Texas, is not the kind of place most people would consider for a summer vacation. It’s miserably hot. Daytime temperatures there would frequently exceed 100 degrees, and nighttime temperatures were not much cooler. But the heat didn’t seem to bother Marney. It wasn’t unusual to see her tending her garden in a housedress and bonnet or wide-brimmed hat.

Marney had been a developer and homebuilder in the years after her husband had passed. She platted a small subdivision in Wichita Falls and built every house in the neighborhood. Her house was like most of the others: two bedrooms, one bathroom, and a carport to shade one car. The only thing that hinted that she had developed the neighborhood was that she had the largest lot. Her house was located near the property line on one side. On the other side of the house, she had a large area with apricot, peach, pecan, and black walnut trees. Behind the house, she had a small grassy lawn. She planted a large fruit and vegetable garden at the back of the yard.

But she knew we weren’t accustomed to the Wichita Falls heat, so she installed a window-unit air conditioner in one of the windows in her living room. She would turn it on as soon as she saw our car in the driveway. It would take a while for the living room to cool down. The kitchen, where we spent most of our indoor time, and the bedrooms never seemed to cool off.

One story my mother tells is about our family spending a night at Marney’s. She had big circulating fans in the bedrooms. They would almost make sleeping tolerable. But when Marney thought everyone was asleep, she would quietly come into the bedroom and turn off the fan. She was frugal to a fault and didn’t want to increase her electric bill if it could be avoided.

Visiting Marney with the Family

As I mentioned, Marney would put us to work when we visited. It may have been mowing the lawn, weeding the garden, or watering the trees and her other plants. She never gave us work as punishment, although sometimes we thought it was. She believed work built character. She was a great role model for the benefit of hard work. She would never ask us to do things that she wouldn’t do herself. I’m not certain that she came up against a chore she couldn’t complete.

But hard work wasn’t all we did with Marney. The Wichita River and Lucy Park were a short distance from her house. Sometimes, we would cut through the acreage behind the house to go to the river. We would take fishing gear, although I don’t remember actually catching fish. But that was more my brother’s thing.

To get to the main part of the park, we would have to cross a swinging bridge. I had a couple of problems with that. First, I was (and remain) terrified of heights. Crossing a largely open, wooden plank bridge was bad enough. But my brother would delight in making the bridge sway or jumping on the slats to make the bridge bounce. It was all I could do to get across. But I wasn’t going to miss out on having fun on the other side.

Going someplace with Marney was a learning experience. She had been a teacher before she married. She remained a teacher at heart. She could tell you about every tree, flower, bird, or rock you would see. The depth of her knowledge of physical science was amazing. Even after she was living in a nursing home, she could sit at the window and tell you all about the plants and birds outside.

In the evenings, the adults would sit around a card table in Marney’s kitchen. They would sometimes play dominos. But more often, the game was canasta or Bolivia. When I was old enough to remember some of the rules, Marney taught me how to play, too. I’m not sure that remembering the rules was all that important. We all thought that Marney made them up as we played. I can still hear her laugh when she won a hand, which was most of the time.

When her fruit trees and garden plants were ripe, Marney would collect the peaches, apricots, and strawberries to make the most delicious preserves I’ve ever tasted. She would also collect the nuts, cracking some and leaving others in the shell. We always went home with boxes full of preserves and nuts to enjoy for months to come.

Two Teens Visit Marney

When I was 15 years old, I took part in what had become a family “rite of passage” with a prolonged visit to Marney’s. I first went to meet up with my second cousin, Mary Alice. She was a year or so older, so she had her driver's license. That was to become important at the end of our visit.

As was to be expected, Marney had plans for both of us during our time there. I did a fair amount of work outside, mowing the lawn, pulling weeds, and watering the yard and fruit trees. Mary was getting expert sewing lessons from Marney. She had made her own clothes for many years and loved passing on her knowledge. By the end of our visit, Mary had a nice new outfit. We were ready to have some fun.

We had made friends with a couple of other teens who lived on Falls Drive. There wasn’t much for teens to do in the immediate area other than crossing the highway to go to the little shopping center. The main feature of the center was a Piggly-Wiggly store. We made a few trips over there to buy cold drinks and junk food that Marney would never have in her house. We were still kids, after all.

When our new friends invited us to join them at a dance on the other side of town, let’s just say Marney was not happy. She was OK with us doing things near the house, but she wasn’t about to have two teens under her supervision going someplace where they might get into trouble. We begged and bargained, but Marney wasn’t going to change her mind. Finally, Mary used the nuclear option. She called her mom (Marney’s elder daughter) while Marney was outside and asked her to intercede. Well, that didn’t work.

A few days later, Mary’s parents arrived at Marney’s house to pick us up. We didn’t know then that they had convinced Marney to give up her car. She was 78 years old and had been in a couple of minor fender-benders, so she agreed it was time to turn in her keys. The result was that Mary and I were to take Marney’s car and follow her parents to her sister’s home about an hour away, largely on country roads.

About halfway there, a huge sow lumbered into the road between Mary’s parents’ car and ours. Mary screamed and slammed on the brakes. Somehow, we managed to miss the pig. But it took a few minutes before she could resume the trip. Her father had seen it all happening in his rearview mirror. He turned around to come back and check on us. I suspect he had a good laugh after determining that we were okay.

Later Visits

I continued to visit Marney as a young adult. By that time, she had moved to West, Texas (a small town North of Waco). At first, she lived in a garage apartment behind my great-aunt and great-uncle, Lee Ellen and B. F Sulak. (Mary Alice’s parents). They were building a new house on some acreage they owned outside of town. Marney decided that she wanted to build a home out there for herself. I wasn’t there during construction, but I heard plenty of stories about it.

Marney had been a home builder in Wichita Falls, so she knew all about what she wanted done with her new house. It was situated a few hundred yards down the hill from the Sulak’s new house. She wanted a small home, two bedrooms, one bath, and a kitchen/living room combination. She had never really used the living room in her former home in Wichita Falls. Guests naturally congregated around the dining table or card table in the kitchen.

She had a carport attached to the house, even though she no longer drove or owned a car. There was a storage room at the back of the carport to hold her lawnmower and gardening tools. Marney was determined to re-create the gardens and trees she had in Wichita Falls. Of course, the house was located on a rocky hill in Central Texas instead of a flat property with red dirt in the northwest part of the state.

Marney supervised every part of the construction of her new house. A carpenter couldn’t hammer a nail in a board without her keen eye on it. She scared everyone when we found out that she had actually climbed up on the roof to be sure the roofers were installing the shingles properly. Did I mention that she was 80 at this time? She had worked hard her entire life, and she wasn’t stopping yet.

With the house finished, she started work on her gardens. She dug countless rocks out of the ground to make flat areas for planting. She saved the rocks to build low stone walls around the garden area. It was an amazing thing to see. Unfortunately, one evening after she had been in the house for a few years, she was digging in her garden, fell, and broke a hip. She managed to drag herself to the carport but couldn’t get into the house. She laid on the carport until the next morning when my great-uncle came down and found her.

After she had largely recovered from her broken hip, the family decided to place her in a local nursing home, knowing how stubborn she could be about doing things around the house. At first, she thought that it was temporary. After time, she accepted that the nursing home was her new home. She didn’t particularly like it. But she adapted.

During this time, both my grandmother and great-aunt passed away. Marney was not one to show a lot of emotion. Her way of dealing with their deaths was to stop talking about them. She also stopped acknowledging anyone related to her children. We could go and visit, she would tell us all about what was going on at the nursing home, what birds she saw outside her window, and sometimes about old friends and distant family. But she never said a word about my grandmother, my great-aunt, or great-uncle who had passed many years earlier.

On what I think was my last visit with her, I had gone alone. We sat and had a good conversation. I was pretty sure she knew who I was, or at least that I was someone who should be visiting with her. But when the announcement was made that bingo would be starting soon in the dining room, she turned to me and said, “You can go now.” She allowed me to wheel her down to the dining room, where we said our goodbyes.

Marney at the nursing home during one of our visits. Photo collection of the author.

Conversations

Marney knew what interested each one of us. She would have different conversations with my brothers and me. She would tell us different stories that she knew we would enjoy. Afterward, we would “compare notes” to see what we heard. For example, on one trip she told my brother about traveling by horse and wagon and seeing Native Americans in the distance. (She may have embellished the story a bit. She certainly was old enough to have traveled in a wagon. But the Native American part is questionable.)

She would only tell us what she wanted us to know. At one time or another, we all heard her say, “I will take that story to my grave.” And she meant it. As I’ve worked on our family genealogy, I’ve learned a lot of things that most families would be proud to discuss. Marney’s ancestors were some of the leading figures in Quaker history. Her 2nd great-uncle had been a congressman and then the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury under Andrew Jackson. But it wasn’t her way to talk about things like that. She was more concerned about how we lived our lives than where we came from.

Marney was 98 when we lost her in 1989. I thought she was going to make it to 100. But she had been ready to go for a long time. She had outlived all three of her children and two of her grandchildren. She was a great role model to all of us in the generations that followed her.

Love this! I could see her West texas place and her rock wall gardens as i read them. I still have one of her famous rose rocks❤️

I really enjoyed getting to know Marney! I like your writing style.